It’s a fantastic time to be a news junkie. I subscribe to Google Alert keywords for religion, health and mental health, as well as news of the Oregon Coast where I live. For an international perspective, I track Al Jazeera, the BBC and Deutsche Welle.

It’s a fantastic time to be a news junkie. I subscribe to Google Alert keywords for religion, health and mental health, as well as news of the Oregon Coast where I live. For an international perspective, I track Al Jazeera, the BBC and Deutsche Welle.

My wife listens to NPR, keeps up with friends and relatives on Facebook, and finds out what’s happening in our neighborhood via NextDoor. We also subscribe to a regional USA Today subsidiary newspaper.

Consequently, I receive around 200 digital news-related alerts each day, and every morning an old-school paper thumps into my front door. As such, we are part of the problem of media bias.

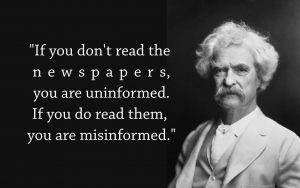

So how could such a broad palette of news sources lead to bias? Media bias comes in many flavors all of which alter or muddy facts with blatant or covert opinion.

In the 1960s, when my parents got their first black-and-white television, CBS, NBC and ABC were the primary electronic news sources. Families watched the Huntley-Brinkley report on NBC, or Walter Cronkite on CBS. Because the airwaves were limited, in 1949 the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) implemented the Fairness Doctrine which required broadcasters to address issues of public concern and to present opposing sides.

In a 1969 Supreme Court case Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. Federal Communications Commission the High Court affirmed the doctrine. Justice White said that without it, station owners would only have people on the air who agreed with their opinions, and that broadcast media should be used to educate the public about controversial issues in a way that is fair and unbiased so they can create their own opinions. Furthermore, the High Court said that the Fairness Doctrine was essential to democracy.

With few broadcast options, networks could not afford to alienate large segments of their viewers and so a fair and balanced approach to reporting was also the best business strategy.

But in 1989 the U.S. Court of Appeals discarded the Fairness Doctrine, saying in part that it “no longer served the public interest.” The decision referenced the FCC’s conclusions that the doctrine chilled “the expression of unorthodox or ‘fringe’ views on controversial issues” and that the doctrine was no longer needed in light of the dramatic increase in broadcasting outlets.

Then in 1993 the Internet became public, and in 2004 MySpace reached 1 million monthly users. Social media leaped out of the box and changed everything.

Today 80 percent of Americans get news via digital devices from literally millions of “broadcasting outlets” providing information of all kinds from pornography to religious programming. Viewers – instead of being presented a balanced news diet – are swamped with all manner of oddities. In that multiplicity of choices, the “unorthodox or fringe views” on controversial issues – which the court sought to empower by killing the fairness doctrine – lurched into prime time and took over.

And in a perfect storm of media confusion, newspapers began to decline, overshadowed by sensational clickbait designed to fascinate, horrify, anger or arouse the reader.

With advertising contingent on metrics such as time on page and ad clickthroughs, why present a balanced issue, when readers were more likely to click on some outrageous or sensational bit of gossip, attack on a religious group, or a public figure’s “costume malfunction.”

Media began to bifurcate politically. AllSides – one outlet that does attempt to show balance in reporting – rates Breitbart, Fox News and the National Review as politically right-wing, and CNN, Democracy Now and Huffington Post as left-wing. Reuters, the Christian Science Monitor, BBC and the Associated Press are rated in the center which does not mean they are unbiased, but “… means the source or writer rated does not predictably publish perspectives favoring either end of the political spectrum — conservative or liberal.”

It is human nature to want to be right in one’s opinions, and today’s “unfair and unbalanced” journalism provides news stovepipes that support most any view, no matter what the opinion or whether it is fact, fancy, half-truth, unorthodox, fringe or just plain nuts.

It appears that the demise of the Fairness Doctrine opened the door for the problems mentioned by Justice White in 1989. “Station owners” do broadcast only those opinions they agree with. And rather than presenting balanced facts that would allow viewers/readers/listeners to draw their own conclusions and form their own opinions, media pre-package what one should think. And thus the fringes now hollow out the middle.

In my morning news beat, I do not expect nor do I find balanced reporting on issues except in a very few treasured sources, mainly middle-of-the-road media like those mentioned above.

Is there a solution – a Fairness Doctrine 2.0 – that can restore balanced reporting and faith in the media in a time of polarized opinions, “fake news” and deep political and social scars? And can it be done without trampling the First Amendment? Former Congresswoman and 2020 presidential candidate Tulsi Gabbard in 2019 introduced the “Restore the Fairness Doctrine Act of 2019” but it died in Congress.

Nevertheless, The Winter 2020 Hastings Law Journal carries an examination of Fairness Doctrine 2.0 that concludes: “The United States is faced with a crisis of distrust in the media the likes of which it has never seen before. Abject media bias and online fake news have created a situation in which most Americans cannot even name an unbiased news source. Because of its ability to hold broadcasters accountable for the objectivity of their content, Fairness Doctrine 2.0 would go a long way towards healing the wounds that media bias and fake news have inflicted on American discourse. At the end of the day, however, the burden to think critically, question suspect claims, get information from reputable sources, and hold media outlets accountable for the accuracy and objectivity of their reporting lies upon us as consumers of media.”

So if it’s up to us, what can we do? First, I treasure my regional newspaper because it does balance its reporting, and even alternates liberal and conservative political cartoons, so I feel like the writers and editors are not trying to browbeat me into a predetermined point of view. In such an environment I find myself much more willing to examine other viewpoints — and that’s something worth supporting.

By Wayne Edward Hanson, first published in Standleague.org