A hundred years ago, traveling shows peddled patent medicine, sometimes one step ahead of the authorities. Ingredients included opium, alcohol, laudanum, radium, and other illicit substances. Tapeworm larvae were sometimes suspended in weight-reduction remedies.

A hundred years ago, traveling shows peddled patent medicine, sometimes one step ahead of the authorities. Ingredients included opium, alcohol, laudanum, radium, and other illicit substances. Tapeworm larvae were sometimes suspended in weight-reduction remedies.

By the time the authorities closed in, the wagon, the salesman and his wares were gone, leaving the purchaser or the local doctor to deal with the side effects of the medication: addiction, parasite infestation, cancer or worse. In 2018, we may look at such abuses as a long-gone product of unbridled greed and horrific ignorance, that could not exist in our highly connected and well-educated society of today.

However, indications exist of a modern-day version of yesteryear’s patent medicine traveling show.

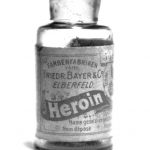

During the Civil War, for example, morphine was used as a painkiller for wounds. But many patients given the drug for pain became addicted. To counter the addictive nature of morphine, heroin – supposedly less addictive – was developed by Bayer and was widely adopted for pain reduction. Problem solved – at least until the addictive properties of heroin were manifest.

In 1947, Methadone – an opioid developed by Germany’s IG Farben in the 1930s – was approved for use in the United States to get addicts off heroin. But while the half-life of morphine is one to five hours, and heroin’s half-life is 30 minutes, Methadone’s half-life is 24 hours to 50 hours or more. That makes it useful for maintenance, as addicts can receive a dose in a registered facility once per day, but it makes getting completely off the drug very difficult.

For example, April, a former heroin counselor who does not wish to be identified, said that “in the 1970s, heroin addicts were being channeled to methadone maintenance as a way of stably getting off heroin. The heroin addict would go to a Methadone maintenance program that was fully funded at no out-of-pocket expense to the addict, and receive a daily dose of Methadone.”

Methadone, said April, did not provide the high but did eliminate the physical withdrawal symptoms, and allowed the addict a more stable life. They didn’t have to steal, they could hold a job, and have a somewhat manageable life as long as they went for their daily doses of Methadone. But there was a cost.

“Methadone had a much harder and longer detox period, so if the addict ever wanted to come off maintenance, they were in for a very uncomfortable ride.” Because of that, April’s non-profit detox unit couldn’t handle Methadone detox. “The street guidance,” she said, “was to spend three weeks or so to transition from Methadone back to heroin, and then check into heroin detox and in 3-10 days you were through withdrawal and could go back to the ‘manageable life’ you’d established while on Methadone maintenance.” At that point the addict was drug free but beset with cravings which had been kept at a distance with Methadone.

So why would an addict want to come off Methadone maintenance? “They have to show up at a clinic seven days a week,” said April, “line up with other junkies for their dose of the drug, so they are still a slave to the drug. They became a functional Methadone addict rather than a dysfunctional heroin addict.”

Methadone, as does any opioid, also fosters physical dependence, and long-term use can cause damage to nerves, liver and brain. Perhaps maintenance is an acceptable risk compared to the dangers of dirty needles, overdoses in alleys and robbing liquor stores or engaging in prostitution to secure the hundreds of dollars a day necessary to feed a raging drug habit, but nonetheless it is a far cry from being free of drug slavery.

Because of the dangers of addiction, physicians were reluctant to prescribe opioids for pain, except in the most severe cases. But in 1996, Purdue Pharma launched OxyContin as a timed-release supposedly non-addictive opioid pain reliever. Reassured, physicians began prescribing it.

Contrary to Purdue’s assertion of non-addiction, the FDA recently said OxyContin is more addictive than morphine. So once again, a drug solution becomes the next problem, as evidenced by the “opioid crisis” spurred by OxyContin and other pharmaceuticals. In 2016, according to the New York Times, 64,000 people were killed by drug overdoses of prescription opioid painkillers and heroin. And drug addiction costs the country $78.5 billion a year in healthcare, lost productivity, addiction treatment and criminal justice.

This problem/solution/problem theme continues today under the title of Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) which substitutes a legally prescribed drug such as Methadone, Naltrexone or Buprenorphine for an illegal street drug. MAT is spreading across the country as a solution to the opioid crisis, embraced by cities, counties, states and even prison systems.

One hundred years ago, purveyors of dangerous patent medicine could slip away undetected. But today – with our electronic medical records and coordinated law enforcement systems – we might expect immediate action against such dangers. But OxyContin and its role in the opioid crisis took two decades to spot, with disastrous consequences.

For that reason, prescribing pharmaceuticals as solutions for addiction should be looked at with some skepticism. This is even more important as a rush of breathless reports appear in popular media about the benefits of LSD, ecstasy and marijuana as solutions for depression, PTSD, and more.

By the time we detect the harmful nature of these so-called remedies, the patent-medicine salesman has stuffed the cash into his pockets and moved on, while communities are left to pick up the pieces.